Figure and Ground in Music

One may also look for figures and grounds in music. One analogue is the distinction between melody and accompaniment--for the melody is always in the forefront of our attention, and the accompaniment is subsidiary, in some sense. Therefore it is surprising when we find, in the lower lines of a piece of music, recognizable melodies. This does not happen too often in post-baroque music. Usually the harmonies are not thought of as foreground. But in baroque music--in Bach above all--the distinct lines, whether high or low or in between, all acts as "figures". In this sense, pieces by Bach can be called "recursive".

Another figure-ground distinction exists in music: that between on-beat and off-beat. If you count notes in a measure "one-and, two-and, three-and, four-and", most melody-notes will come on numbers, not on "and"'s. But sometimes, a melody will be deliberately pushed onto the "and"'s, for the sheer effect of it. This occurs in several études for the piano by Chopin, for instance. It also occurs in Bach--particularly in his Sonatas and Partitas for unaccompanied violin, and his Suites for unaccompanied cello. There, Bach manages to get two or more musical lines going simultaneously. Sometimes he does this by having the solo instrument play "double-stops"--two notes at once. Other times, however, he puts one voice on the on-beats, and the other voice on the off-beats, so the ear separates them and hears two distinct melodies weaving in and out, and harmonizing with each other. Needless to say, Bach didn't stop at this level of complexity ...

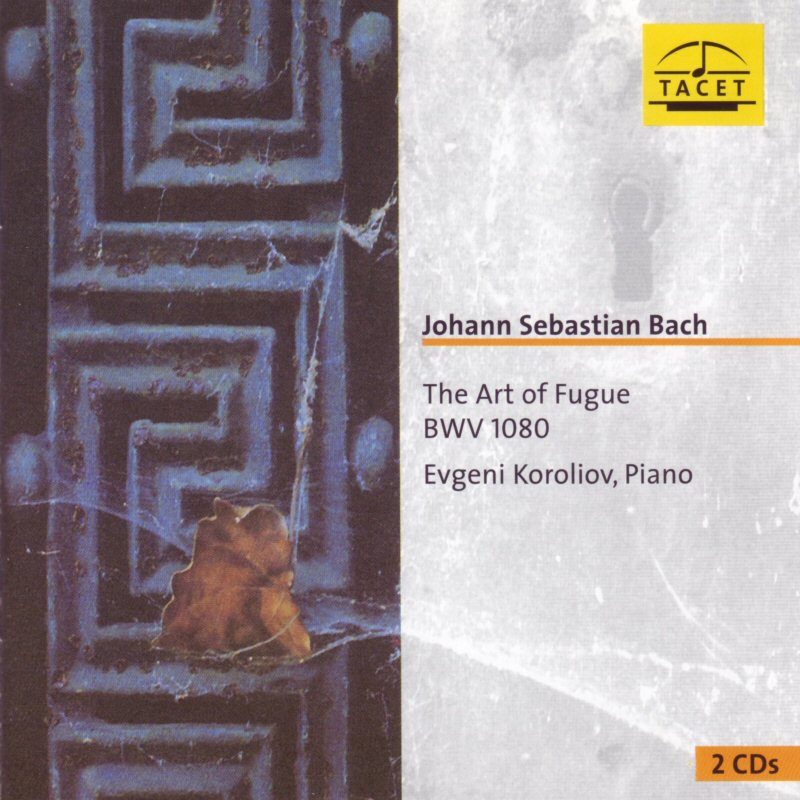

The Art of the Fugue

A few words on the Art of the Fugue ... Composed in the last year og Bach's life, it is collection of eighteen fugues all based on one theme. Apparently, writing the Musical Offering was an inspiration to Bach. He decided to compose another set of fugues on a much simpler theme, to demonstrate the full range of possibilites inherent in the form. In the the Art of the Fugue, Bach uses a very simple theme in the most complex possible ways. The whole work is in a single key. Most of the fugues have four voices, and they gradually increase in complexity and depth of expression. Toward the end, they soar to such heights of intricacy that one suspects he can no longer maintain them. yet he does ... until the last Contrapunctus.

The circumstances which caused the break-off of the Art of the Fugue (which is to say, of Bach's life) are these: his eyesight having troubled him for years, Bach wished to have an operation. It was done; however, it came out quite poorly, and as a consequence, he lost his sight for the better part of the last year of his life. This did not keep him from vigorous work on his monumental project, however. His aim was to construct a complete exposition of fugal writing, and usage of multiple themes was one important facet of it. In what he planned as the next-to-last fugue, he inserted his own name coded into notes as the third theme.

Bar 235 " B A C H "

However, upon this very act, his health became so precarious that he was forced to abandon work on his cherished project. In his illness, he managed to dictate to his son-in-law a final chorale prelude, of which Bach's biographer Forkel wrote, "The expression of pious resignation and devotion in it has always affected me whenever I have played it; so that I can hardly say which I would rather miss--this Chorale, or the end of the last fugue."

One day, without warning, Bach regained his vision. But a few hours later, he suffered a stroke; and ten days later, he died, leaving it for others to speculate on the imcompleteness of the Art of the Fugue. Could it have been caused by Bach's attainment of self-reference?

Det allerførste jeg gerne ville høre er "Suites for unaccompanied cello".

Jeg er nu meget glad for Argerich, og ved ikke hvorfor jeg ikke lige tror på hende i well tempered, fordi nedenstående Bach plade er et stykke unika. Tindrende, perlende, vitalt. Et MUST.

Jeg er nu meget glad for Argerich, og ved ikke hvorfor jeg ikke lige tror på hende i well tempered, fordi nedenstående Bach plade er et stykke unika. Tindrende, perlende, vitalt. Et MUST.