Pling! - Klassisk for begyndere

17 indlæg

• Side 1 af 2 • 1, 2

Pling! - Klassisk for begyndere

God aften

Jeg sad her til morgen og lyttede til P2's nye program "Pling! - Klassisk for begyndere" og må sige at jeg blev positivt overrasket. Jeg har selv gennem et stykke tid haft store problemer med at finde ud af hvad man skal lytte til når men gerne vil i gang med at lytte til noget klassisk musik, for mængden af musik indenfor denne genre er jo enorm!

Jeg synes at dette nye program på en meget let og behagelig måde introducerer noget klassisk musik, og så efterfølgende behandler det enkelte stykke musik, kan kun anbefale andre at lytte til det første program, som kan findes på følgende adresse: http://www.dr.dk/P2/Pling/pling.htm. For mig var dette første program i hvert tilfælde en succes, håber også andre kunne have glæde af det, nu glæder jeg mig til på næste lørdag  .

.

- Dr-Tricket

- Medlem

- Indlæg: 93

- Tilmeldt: lør dec 17, 2005 16:08

- Geografisk sted: Nordjylland

Re: Pling! - Klassisk for begyndere

Dr-Tricket skrev:Jeg har selv gennem et stykke tid haft store problemer med at finde ud af hvad man skal lytte til når men gerne vil i gang med at lytte til noget klassisk musik, for mængden af musik indenfor denne genre er jo enorm!

Et andet alternativ kan være den gamle kending http://www.pandora.com/. Der har jeg i hvert fald selv fået udvidet min musikhorisont betydelig.

Gør dig selv, og de andre brugere af forummet, den tjeneste at lære korrekt citatteknik.

-

zerocool - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 1462

- Tilmeldt: fre dec 30, 2005 23:18

- Geografisk sted: Århus C

Re: Pling! - Klassisk for begyndere

zerocool skrev:Et andet alternativ kan være den gamle kending http://www.pandora.com/. Der har jeg i hvert fald selv fået udvidet min musikhorisont betydelig.

Også til klassisk musik? det har jeg ikke kunnet få den til

____________________________________

I like my hifi black like my men

I like my hifi black like my men

-

Bulgroz - Seniormedlem

- Indlæg: 731

- Tilmeldt: tirs okt 25, 2005 21:57

Måske man skulle prøve det!

Nu vi er ved det...:

SES skrev engang en artikel med et par anbefalinger til start af klassisk lytning.. men den kan jeg ikke finde her på siden længere... er den blevet helt væk mon?

Nu vi er ved det...:

SES skrev engang en artikel med et par anbefalinger til start af klassisk lytning.. men den kan jeg ikke finde her på siden længere... er den blevet helt væk mon?

- Snn

- Nyt medlem

- Indlæg: 19

- Tilmeldt: ons dec 07, 2005 11:34

- Geografisk sted: Nordjylland

Hej Dr Trick

Det er altid dejligt at læse dine alt for få indlæg. Jeg skal prøve at huske næste lørdag, selvom DR2 nu har lukket deres bedste program ”Søndagsklassikeren” er det stadig den kanal med flest input til øverste etage.

Hvilken musik har du indtil nu syntes godt om?

Du har sikkert set: http://www.hifi-musik.dk/?page=viewtopic&t=86 Dog ingen konkurrence for et godt radioprogram.

Det er altid dejligt at læse dine alt for få indlæg. Jeg skal prøve at huske næste lørdag, selvom DR2 nu har lukket deres bedste program ”Søndagsklassikeren” er det stadig den kanal med flest input til øverste etage.

Hvilken musik har du indtil nu syntes godt om?

Du har sikkert set: http://www.hifi-musik.dk/?page=viewtopic&t=86 Dog ingen konkurrence for et godt radioprogram.

mvh. SES.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

-

SES. - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 2578

- Tilmeldt: tirs okt 25, 2005 06:58

- Geografisk sted: Midtfyn

SES. skrev:Hej Dr Trick

Det er altid dejligt at læse dine alt for få indlæg. Jeg skal prøve at huske næste lørdag, selvom DR2 nu har lukket deres bedste program ”Søndagsklassikeren” er det stadig den kanal med flest input til øverste etage.

Hvilken musik har du indtil nu syntes godt om?

Du har sikkert set: http://www.hifi-musik.dk/?page=viewtopic&t=86 Dog ingen konkurrence for et godt radioprogram.

Ja pt. har jeg mest lyttet til Mozart, og så nogle få med Bach bl.a. Goldberg Variations, med Murai Perahia  , og har det meste af dagen i dag lyttet til Brandenburg koncerterne, nøj de er godt fantastisk gode... nu mangler jeg bare et tip til en god indspilning

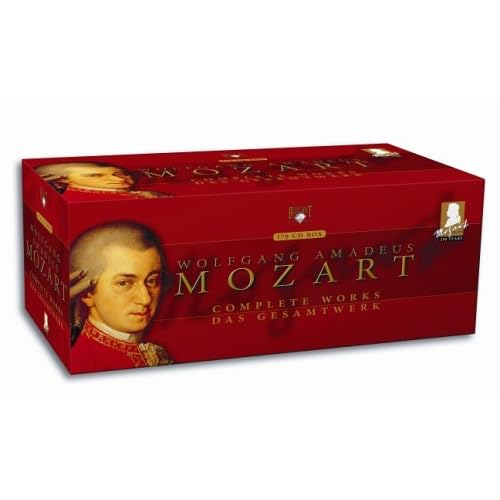

, og har det meste af dagen i dag lyttet til Brandenburg koncerterne, nøj de er godt fantastisk gode... nu mangler jeg bare et tip til en god indspilning  . Kan specielt godt lide koncert nummer fem, synes altså at det cembalo lyder helt fantastisk. Ellers har jeg lige investeret i følgende boks:

. Kan specielt godt lide koncert nummer fem, synes altså at det cembalo lyder helt fantastisk. Ellers har jeg lige investeret i følgende boks:

Godt nok en ordentlig mundfuld, men kan generelt godt lide hans musik, og så kan man jo lige så godt købe det hele på en gang .

.

- Dr-Tricket

- Medlem

- Indlæg: 93

- Tilmeldt: lør dec 17, 2005 16:08

- Geografisk sted: Nordjylland

Hvis man kan se Sverige 2, så kunne f.eks også blænde op for (kl. 19:00):

Ugens koncert: Grosse Messe

Ballet af Uwe Scholz til Mozarts messe.

Med Leipzig-balletten, operakoret og Gewandhaus-orkestret.

Dirigent: Balázs Kocsár.

Jeg kan godt lide at nuppe det sungne på TV til at starte med

- så man har underteksterne til at hjælpe sig med at lære historien at kende!

Det var f.eks først igår jeg fandt ud af hvad Figaros Bryllup egentlig går ud på

- måske ikke så overraskende; 3,5 times intriger!

Ugens koncert: Grosse Messe

Ballet af Uwe Scholz til Mozarts messe.

Med Leipzig-balletten, operakoret og Gewandhaus-orkestret.

Dirigent: Balázs Kocsár.

Jeg kan godt lide at nuppe det sungne på TV til at starte med

- så man har underteksterne til at hjælpe sig med at lære historien at kende!

Det var f.eks først igår jeg fandt ud af hvad Figaros Bryllup egentlig går ud på

- måske ikke så overraskende; 3,5 times intriger!

-

macwerk - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 1830

- Tilmeldt: fre nov 11, 2005 09:42

macwerk skrev:Hvis man kan se Sverige 2, så kunne f.eks også blænde op for (kl. 19:00):

Ugens koncert: Grosse Messe

Ballet af Uwe Scholz til Mozarts messe.

Med Leipzig-balletten, operakoret og Gewandhaus-orkestret.

Dirigent: Balázs Kocsár.

Jeg kan godt lide at nuppe det sungne på TV til at starte med

- så man har underteksterne til at hjælpe sig med at lære historien at kende!

Det var f.eks først igår jeg fandt ud af hvad Figaros Bryllup egentlig går ud på

- måske ikke så overraskende; 3,5 times intriger!

Jeg fik optaget koncerten i går, nu skal jeg bare have tid til at se den, det er godt nok også en ordentlig omgang at gå i gang med

- Dr-Tricket

- Medlem

- Indlæg: 93

- Tilmeldt: lør dec 17, 2005 16:08

- Geografisk sted: Nordjylland

Dyb respekt – en Mozartianer  . Et lidt sjældent folkefærd man skal have et extra øre indeni hovedet

. Et lidt sjældent folkefærd man skal have et extra øre indeni hovedet  .

.

Figaro: Det var også klassekamp – så meget at operaen blev censureret og ændret. Dengang var herremænd ikke horebukke eller mindre kloge.

Bach: Brandenburg – i dag er no 5 også min favorit, tidligere var det 2 og 4 – ren rock’ roll.

Her er et forslag til brandenburg koncerterne – og husk endelig at få lyttet til de 4 koncertoverturer (se til sidst)

J.S BACH

The Six Brandenburg Concertos

Rinaldo Alessandrini (harpsichord)

Concerto Italiano

Rinaldo Alessandrini

Just when you think there is nothing new to say and nothing more to add to the Brandenburg Concertos' rich interpretive spectrum on disc, along comes Rinaldo Alessandrini. In one fell swoop, the harpsichordist/conductor has created a reference period-instrument version for this century's first decade, shedding revealing light on this done-to-death repertoire without ever losing sight of the music's style and spirit. Because Alessandrini assigns one instrument to a part, the strings and horns interact more pungently than usual in the First Concerto, the Fourth's fugue becomes even more conversational and colorful, and the Sixth's dark-toned lower strings acquire a rare buoyancy. Furthermore, the generally fast tempos never slip onto the proverbial metronomic treadmill, while the slow movements feature unfailingly eloquent and flexible solo playing.

The Fifth's central trio-sonata movement is a case in point, where the flute and violin shape their long lines around the beat without losing awareness of it. It's sort of like classical jazz, and it works wonderfully well. If anything, trumpet soloist Gabriele Cassone sounds more lithe and effortless in this Second than in the excellent version he recorded with Il Giardino Armonico on Teldec. Alessandrini's continuo work soars with imagination, yet it never gets in the way--and what a dazzling, no-holds-barred first-movement cadenza in the Fifth!

There are two bonus tracks. One gives you Bach's earlier 18-bar version of the Fifth's cadenza; the other features Bach's later reworking of the Third's first movement that appeared as Cantata No. 174's Sinfonia, with added horns, oboes, and bassoon. Alessandrini explains his approach to Bach and to these pieces in an accompanying DVD that also includes recording session excerpts. Naïve's gorgeous, crystal-clear engineering seals my sky-high recommendation with a sonic kiss. [11/22/2005]

J.S. BACH

Four Orchestral Suites (Ouvertures) BWV 1066-9

Liliko Maeda (flute)

Bach Collegium Japan

Masaaki Suzuki

BIS- 1431(SACD)

Reference Recording - This One

These performances are magnificent, and offering two SACDs for the price of one makes them a good deal too. There have been many fine recordings of these works, naturally, but few offer this much satisfaction on purely sonic terms--not just the engineering, which is state-of-the-art in both stereo and multi-channel formats, but the actual textures and colors that Masaaki Suzuki coaxes from his ensemble. In truth, it's difficult to make this music sound well. On modern instruments, trumpets and drums tend to muddy the textures without penetrating as they should. Period instruments, on the other hand, offer a variety of problems, including a routinely clattery and overbearing harpsichord continuo, scruffy strings that make the famous "Air" sound positively anorexic, and iffy flute intonation in the B minor suite.

Miraculously, Suzuki has solved all of these problems. His harpsichord is clear but pleasant-toned and discretely balanced. The strings have sufficient body and richness of tone to compete successfully with the oboes and cushion the trumpets and drums in the two works that require them. Textures are wonderfully transparent, and rhythms are ideally clear. The arrangement of the works, with the two big D major suites framing the other two, and the "flute suite" performed with solo strings, makes excellent sense and offers maximum contrast for continuous listening. In this latter work, Liliko Maeda is a terrific soloist, pure in timbre and gifted with the ability to really make the music dance--nowhere more so than in the famous concluding Badinerie, so often mercilessly breathy and rushed, but here the very embodiment of sly wit.

Suzuki's handling of all four initial overtures deserves special mention. He catches the regal, aristocratic quality of the music as have few others, evoking the spirit of Handel (as in the Royal Fireworks Music) as much as Bach. That doesn't mean his tempos are slow or lethargic--far from it. But the music has gravitas and a bigness of conception that's so often missing from period-instrument performances, particularly from the "less is more" school (for the record, Suzuki has six violins, and two each of violas and cellos). Nothing sounds rushed, not even the lively central episodes, which are always gracefully phrased as well as full of energy. In the D major suites, the trumpets and timpani cut through the texture as they should, but Suzuki makes their parts fit logically into their surroundings rather than encouraging the usual, overbearing "screech, blast, and bang" that so often passes for period style.

The various dances are also extremely well characterized, with tempos excellently chosen to emphasize the rhythmic qualities of each. The famous "Air" from the Third suite is serene but never static. The bourées have a nicely physical quality to the rhythm, while the Second suite's Sarabande is wonderfully supple and elegant. The program concludes with a smashing Réjouissance from the Fourth suite, a telling reminder of the fact that Bach conceived these pieces as courtly entertainment. In other words, Suzuki does more than just play the music very well: he evokes its purpose, social milieu, and lavishness of content in such a way that brings the listener as close as possible to Bach himself, and to the circles in which he worked. In this oft-recorded repertoire, that is a tremendous achievement. [9/28/2005]

Figaro: Det var også klassekamp – så meget at operaen blev censureret og ændret. Dengang var herremænd ikke horebukke eller mindre kloge.

Bach: Brandenburg – i dag er no 5 også min favorit, tidligere var det 2 og 4 – ren rock’ roll.

Her er et forslag til brandenburg koncerterne – og husk endelig at få lyttet til de 4 koncertoverturer (se til sidst)

J.S BACH

The Six Brandenburg Concertos

Rinaldo Alessandrini (harpsichord)

Concerto Italiano

Rinaldo Alessandrini

Just when you think there is nothing new to say and nothing more to add to the Brandenburg Concertos' rich interpretive spectrum on disc, along comes Rinaldo Alessandrini. In one fell swoop, the harpsichordist/conductor has created a reference period-instrument version for this century's first decade, shedding revealing light on this done-to-death repertoire without ever losing sight of the music's style and spirit. Because Alessandrini assigns one instrument to a part, the strings and horns interact more pungently than usual in the First Concerto, the Fourth's fugue becomes even more conversational and colorful, and the Sixth's dark-toned lower strings acquire a rare buoyancy. Furthermore, the generally fast tempos never slip onto the proverbial metronomic treadmill, while the slow movements feature unfailingly eloquent and flexible solo playing.

The Fifth's central trio-sonata movement is a case in point, where the flute and violin shape their long lines around the beat without losing awareness of it. It's sort of like classical jazz, and it works wonderfully well. If anything, trumpet soloist Gabriele Cassone sounds more lithe and effortless in this Second than in the excellent version he recorded with Il Giardino Armonico on Teldec. Alessandrini's continuo work soars with imagination, yet it never gets in the way--and what a dazzling, no-holds-barred first-movement cadenza in the Fifth!

There are two bonus tracks. One gives you Bach's earlier 18-bar version of the Fifth's cadenza; the other features Bach's later reworking of the Third's first movement that appeared as Cantata No. 174's Sinfonia, with added horns, oboes, and bassoon. Alessandrini explains his approach to Bach and to these pieces in an accompanying DVD that also includes recording session excerpts. Naïve's gorgeous, crystal-clear engineering seals my sky-high recommendation with a sonic kiss. [11/22/2005]

J.S. BACH

Four Orchestral Suites (Ouvertures) BWV 1066-9

Liliko Maeda (flute)

Bach Collegium Japan

Masaaki Suzuki

BIS- 1431(SACD)

Reference Recording - This One

These performances are magnificent, and offering two SACDs for the price of one makes them a good deal too. There have been many fine recordings of these works, naturally, but few offer this much satisfaction on purely sonic terms--not just the engineering, which is state-of-the-art in both stereo and multi-channel formats, but the actual textures and colors that Masaaki Suzuki coaxes from his ensemble. In truth, it's difficult to make this music sound well. On modern instruments, trumpets and drums tend to muddy the textures without penetrating as they should. Period instruments, on the other hand, offer a variety of problems, including a routinely clattery and overbearing harpsichord continuo, scruffy strings that make the famous "Air" sound positively anorexic, and iffy flute intonation in the B minor suite.

Miraculously, Suzuki has solved all of these problems. His harpsichord is clear but pleasant-toned and discretely balanced. The strings have sufficient body and richness of tone to compete successfully with the oboes and cushion the trumpets and drums in the two works that require them. Textures are wonderfully transparent, and rhythms are ideally clear. The arrangement of the works, with the two big D major suites framing the other two, and the "flute suite" performed with solo strings, makes excellent sense and offers maximum contrast for continuous listening. In this latter work, Liliko Maeda is a terrific soloist, pure in timbre and gifted with the ability to really make the music dance--nowhere more so than in the famous concluding Badinerie, so often mercilessly breathy and rushed, but here the very embodiment of sly wit.

Suzuki's handling of all four initial overtures deserves special mention. He catches the regal, aristocratic quality of the music as have few others, evoking the spirit of Handel (as in the Royal Fireworks Music) as much as Bach. That doesn't mean his tempos are slow or lethargic--far from it. But the music has gravitas and a bigness of conception that's so often missing from period-instrument performances, particularly from the "less is more" school (for the record, Suzuki has six violins, and two each of violas and cellos). Nothing sounds rushed, not even the lively central episodes, which are always gracefully phrased as well as full of energy. In the D major suites, the trumpets and timpani cut through the texture as they should, but Suzuki makes their parts fit logically into their surroundings rather than encouraging the usual, overbearing "screech, blast, and bang" that so often passes for period style.

The various dances are also extremely well characterized, with tempos excellently chosen to emphasize the rhythmic qualities of each. The famous "Air" from the Third suite is serene but never static. The bourées have a nicely physical quality to the rhythm, while the Second suite's Sarabande is wonderfully supple and elegant. The program concludes with a smashing Réjouissance from the Fourth suite, a telling reminder of the fact that Bach conceived these pieces as courtly entertainment. In other words, Suzuki does more than just play the music very well: he evokes its purpose, social milieu, and lavishness of content in such a way that brings the listener as close as possible to Bach himself, and to the circles in which he worked. In this oft-recorded repertoire, that is a tremendous achievement. [9/28/2005]

mvh. SES.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

-

SES. - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 2578

- Tilmeldt: tirs okt 25, 2005 06:58

- Geografisk sted: Midtfyn

Ja har lige undersøgt lidt om den version af Brandenburg koncerterne du nævner, og den ahr da også fået en del priser for bl.a. lydkvalitet. Men puha hvor kan den her hoby godt nok ende med at blive dyr

- Dr-Tricket

- Medlem

- Indlæg: 93

- Tilmeldt: lør dec 17, 2005 16:08

- Geografisk sted: Nordjylland

Hej Kasper!

Jamen dyrt kan det hurtigt blive, og anmeldere har det med at friste! Man behøver nu sjældent at købe sidste nye/dyre udgaver. Jeg spiller gerne mine gamle plader selvom de er ”overhalet” af ny viden.

Her er et par billigere alternativer – musikken findes i et utal af indspilninger. Måske har din pusher et billigt og godt sæt stående.

Bare et par muligheder:

BACH J.S.6 Brandenburg Concertos, 4 Orchestral Suites. The English Concert / Trevor Pinnock. Archiv 3cds

£ 14.50

BACH Brandenburg Concertos Orchestra of the age of Enlightenment / Monica Huggett Virgin 2cds

£ 6.50

Jamen dyrt kan det hurtigt blive, og anmeldere har det med at friste! Man behøver nu sjældent at købe sidste nye/dyre udgaver. Jeg spiller gerne mine gamle plader selvom de er ”overhalet” af ny viden.

Her er et par billigere alternativer – musikken findes i et utal af indspilninger. Måske har din pusher et billigt og godt sæt stående.

Bare et par muligheder:

BACH J.S.6 Brandenburg Concertos, 4 Orchestral Suites. The English Concert / Trevor Pinnock. Archiv 3cds

£ 14.50

BACH Brandenburg Concertos Orchestra of the age of Enlightenment / Monica Huggett Virgin 2cds

£ 6.50

mvh. SES.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

-

SES. - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 2578

- Tilmeldt: tirs okt 25, 2005 06:58

- Geografisk sted: Midtfyn

Bulgroz skrev:Dr-Tricket skrev:Ja nu har jeg lige modtaget min Mozart boks, så nu skal jeg have lyttet til 170 cd'erVi ses i 2008

10 Cd'er om dagen, skal vi sige 3 uger .

.

mvh. SES.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

To listen is an effort, and just to hear is no merit. A duck hears also. Igor Stravinsky

Vi har alle lært at skjule vore fordomme, og vi viser ikke vore forkerte meninger. PO Enquist 1976.

-

SES. - Supermedlem

- Indlæg: 2578

- Tilmeldt: tirs okt 25, 2005 06:58

- Geografisk sted: Midtfyn

17 indlæg

• Side 1 af 2 • 1, 2

Hvem er online

Brugere der læser dette forum: Ingen tilmeldte og 1 gæst